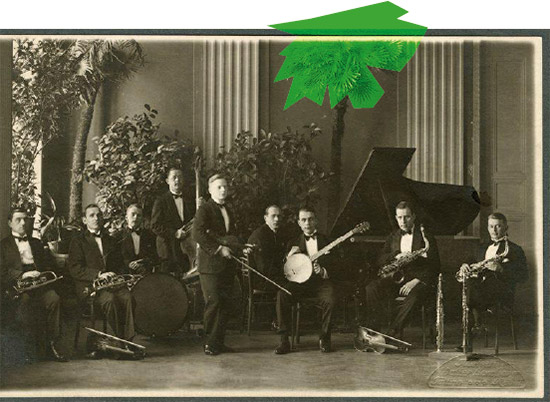

The beginnings of Estonian jazz go back to the summer of 1918 and to a certain dance band that was formed by a bunch of schoolboys in Tallinn, at one of the Estonian capital’s Germanlanguage schools. Initiated by one Kurt Strobel, this band set out to play the modern tunes of the time. In the middle of the 1920s, the nucleus of the aforementioned band founded Estonia’s first professional jazz orchestra, The Murphy Band.

Before WWII, there were approximately 60 dance bands working in Tallinn, some of them enduring longer than others. The fact that jazz music of the era was tightly linked to popular dance styles meant that a remarkable number of players and singers came in contact with the new and exciting musical phenomenon.

In 1936, a first jazz concert in a philharmonic hall took place in Tallinn. The late-1930s swing craze and contemporary dance music swept over Estonia as well. All in all, the Estonian music scene was nicely in sync with the rest of the world.

Below: Members of the orchestra Blackheads Club: left 4. Markus Dubrovkin, 5. Raimond Valgre, 8. Artur Ranne. 1934

WWII ruthlessly disrupted all this. Under the German occupation anything American, including jazz, was strictly verboten. Next, the Soviet occupation followed. Then, for precious few years, there seemed to appear a slight glimmer of hope for jazz – enthusiasts managed to form bands; thanks to a number of American movies being shown briefly in cinemas, Glenn Miller’s “Moonlight Serenade” beamed from silver screens and worked its swing magic once again; and Estonia’s own legendary master of suave swing numbers, Raimond Valgre, composed some of his best songs – and yet, but of course, that was not to last. Not yet.

In the late 1940s, with the advent of the Cold War, everything American, including jazz, was – surprise, surprise? – declared the arch enemy. From Moscow’s Red Square to the most remote corners of the hapless empire, an ominous slogan resounded loud and clear: “Today you play the saxophone – tomorrow you betray your country!” Saxophones were removed from the orchestras; jazzy sounds in any piece of music could, and did, entail severe consequences for composers and performers alike.

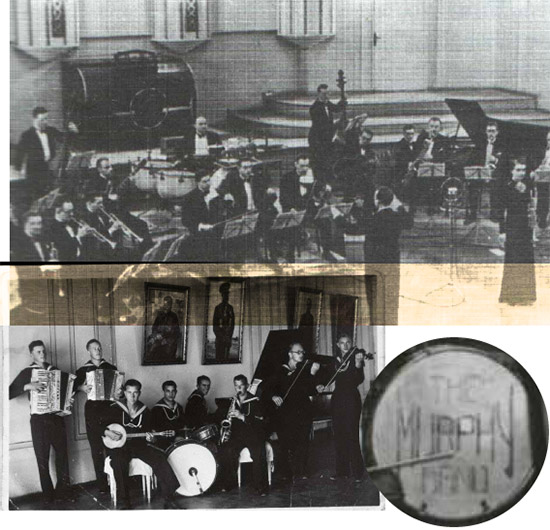

Jazz went underground. In May 1949 in Tallinn, in a clandestine manner, a little jazz festival was held behind closed doors. Roughly ten different line-ups, all of them drawing on the personnel of exactly two orchestras, performed at this event. In the 1950s, launched secretly by some ardent aficionados in Tallinn, a remarkable new club – the Swing Club – quietly sprang into action. This was a serious lot who, by way of discussions and making music together, tried to get the hang of that thrilling new thing called be-bop.

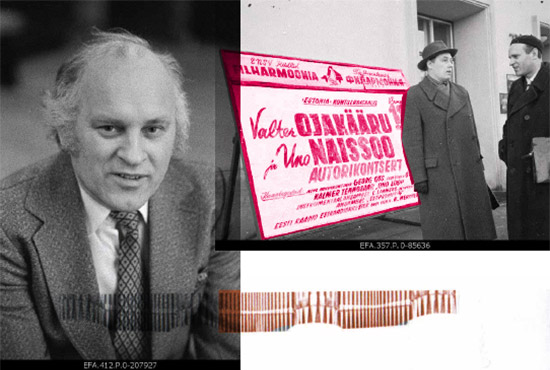

Composers Valter Ojakäär ja Uno Naissoo (right) chatting. February 1961

One of the leaders of this influential circle was composer and educator Uno Naissoo, the most significant innovator in Estonian jazz after WWII. His symbiosis of local folklore and American West-Coast jazz is viewed by many as the starting point of the Estonian national school of jazz.

In 1956 the deadly ideological permafrost began to melt. The saxophone was heard again, loud and proud. First, the Estonian Radio Light Music Orchestra recorded a handful of jazzy sounding dance tune. Emboldened by their example, other musicians followed suit.

More and more, one of the most distinctive features of Estonian jazz started to manifest itself – a great number of the instrumentalists and composers had solid classical training and this fact did left its mark on the music, for generations.

Internationally renowned conductors Neeme Järvi and Eri Klas, for instance, played in jazz bands in their youth. Many a member of the Estonian Composers Union wrote jazz-tinged songs and instrumental or performed with jazz bands themselves.

Alongside Uno Naissoo, two other outstanding advocates of the jazz cause were swing music enthusiasts Valter Ojakäär and Aleksander Rjabov. The latter was also audibly enamoured of bossa nova.

In 1959, instigated by Uno Naissoo, a modest jazz festival was organised in Tallinn. From this, a new tradition was about to sprout. The Soviet authorities of the time, however, were still vastly suspicious of jazz – a malevolent form of alien Western music, in their estimation – and thus every step in that direction meant trouble and strife for the musicians.

Nevertheless, jazz festivals continued to take place and the number of top musicians from different parts of the Soviet Union appearing at these evens was on the rise. In 1966, the Tallinn Jazz Festival turned international. As for the scope and significance of the 1967 festival, legendary is evidently the appropriate term. The headliner was the Charles Lloyd Quartet, then at the peak of its popularity – performing on the other side of the Iron Curtain! The message that jazz was held in great esteem in Estonia was spread globally by the New York Times, the Voice of America and the Down Beat Magazine.

Shortly after that the ideological barriers came crashing down once more and the jazz festival tradition was cut off.

Below: Charles Lloyd, Anne Erm and Lloyds wife Dorothy Darr at Tallinn Airport. 1997

It would take years to recover, yet the next generation of musicians managed to draw on the positive impulse of the past and move on. For jazz in Estonia in general, the splendid status of yore was gone forever – but the same process was underway all over the world. Everywhere, jazz was losing listeners galore to rock and pop music.

Jazz adapted and adjusted itself to changes. New rhythms and contemporary sounds introduced. Electronics, fresh beats and jazz-rock existed side by side with the trends and traditions of previous decades. Estonia’s best jazz musicians – saxophonist Lembit Saarsalu, guitarist Tiit Paulus, multiinstrumentalist Helmut Aniko, sax player Arvo Pilliroog – were among the best jazz instrumentalists of the Entire ‘Soviet Union.

From the late 1980s the red empire started to crumble and the subsequent historic turmoil, shaking pretty much everything to its foundation, did not leave jazz music untouched. Another reality check was in order.

With Estonia regaining its independence and the Iron Curtain gone, the whole wide world suddenly appeared open for everybody, our music and musicians included. It was a sobering experience to learn, though, that there actually was no place to go, not initially anyway. Nope, no welcoming committees waiting on the other side. Estonian jazz had to restart almost from scratch – relearn a lot of things, find its audience, make new friends near and afar, keep up with the times, be open for every opportunity and be ready to grab every chance.

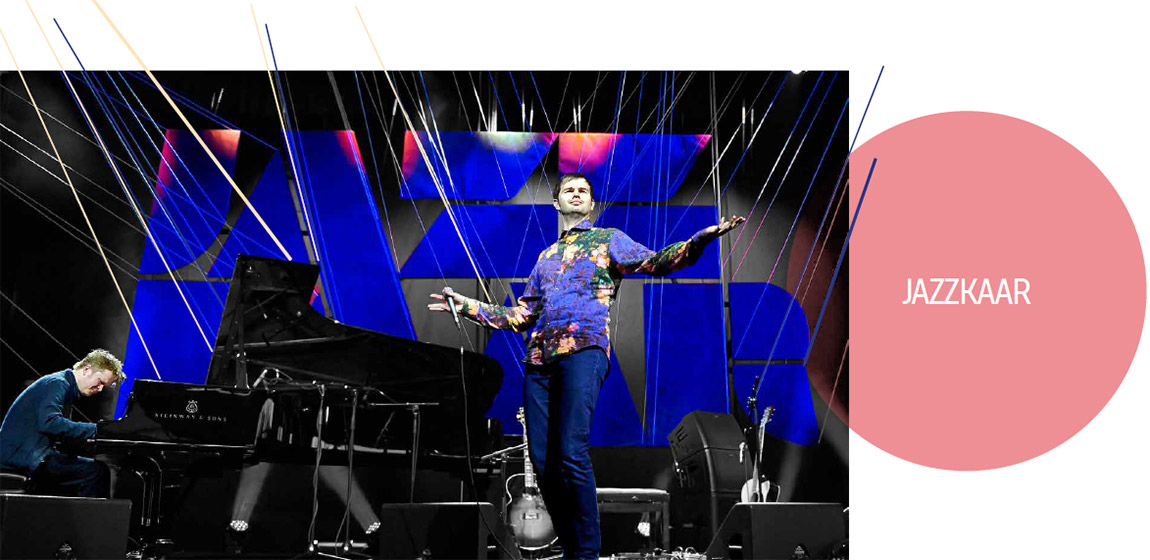

Launched in 1990, the annual festival Jazzkaar became an important catalyst. Jazzkaar – the Tallinn International Festival Jazzkaar, as it is currently called – was the forum where Estonian musicians presented their new work and fresh recordings, where they could admire the craft of famous foreign artists and sometimes learn from them first-hand, be it at jam sessions or occasional workshops.

It was in the 1990s that a young generation of Estonian jazzers went abroad to study, to improve their skills, to gain experience and make contacts. Estonian jazz found its way into the world, step by step, via the Nordic countries and the Baltic States.

The Estonian jazz of today is modest in size and number, for Estonia itself is a small country. In spite of that, Estonian jazz certainly shows variety, openness, vitality, creativity and lots of youthful energy. Being small in number does have its limits as well as advantages – many of our jazz musicians are musical “polyglots”, performing in classical ensembles and orchestras, with folk and experimental line-ups and rock bands and. So on.

The Estonian jazz scene bursts with robust activity. Compared to their predecessors, the young-Est jazz generation is more numerous, more open, better trained and educated in many ways.

The groundwork for jazz education in Estonia was laid by Uno Naissoo, whose abiding enthusiasm and hard work led to establishing the department of popular music – or rhythm music, as it is known today – at the then Georg Ots Tallinn Music School. Renamed the Georg Ots Tallinn Music College long since then, this honourable institution has been the breeding ground for countless young jazz talents in Estonia.

From 2004 at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, jazz studies are part of the academic curriculum, too. And in addition to Tallinn, jazz is taught in earnest also in Viljandi (the University of Tartu Viljandi Cultural Academy) and in Tartu (the Heino Eller Music School).

Founded also in 2004, the Jazz Estonia has added its own indispensable momentum to the proceedings, bringing the musicians closer together locally as well as expanding their creative horizons internationally.

As regards the capital of Estonia, jazz gigs take place with laudable regularity at the Theatre No99 Jazz Club and at Philly Joe’s.

On the festival scene, in addition to the positively venerable Jazzkaar, a couple of more deserve to be mentioned here and now in the late 2010s: the Student Jazz Festival (Tudengijazz, operative since 1982), and also the somewhat exotically named Juu Jääb fest (Will Go On, as it were), taking place on the Isle of Muhu and running for nearly a decade now. Then there’s also, held in two cities that‘re rather far from each other, the festival IdeeJazz, taking place in both Tartu and Narva.

Since 2007, the Tallinn International Festival Jazzkaar in collaboration with the Jazz Estonia have presented the annual Estonian Jazz Awards in several categories – to the most outstanding jazz musician of the year, the young jazz talent, the fosterer of the jazz culture of the year, etc., etc. & so on.

Parallel to that, the Estonian Association of the Phonogram Producers (EFÜ) have been handing out their own award for the jazz album of the year, since the year 2000.

Speaking of the most internationally renowned Estonian jazz musicians of recent times, one cannot but take note of the ECM recording artist, versatile pianist-bandleader–composer Kristjan Randalu and also the saxophonistcomposer-bandleader Maria Faust.

Amongst the other active-and-upcoming talents – bound to break unto the outer national scene with any number of their various line-ups, any time soon – one should consider the band leaders-composers Kirke Karja (keyboards), Kadri Voorand (vocals, electronics, keyboards), Jaak Sooäär (guitar etc etc), Peedu Kass (bass, and so on), Tanel Ruben (drums & percussion &), Joel Remmel (keyboards & composition &) and Erki Pärnoja (guitars, electronics, and so on).

Of the elder generation, still alive and very much kickin’, are saxophonist Lembit Saarsalu, keyboardist Tõnu Naissoo, plus saxmen-composers Raivo Tafenau and Raul Sööt. What’s more, there are also the indomitable guitar-slinger-slash-band(co)leader-composer Mart Soo, bass-slinger-composer Taavo Remmel, and bandleaderpercussion-master-composer Toomas Rull.

In a nutshell, the incessant features of the contemporary Estonian jazz scene would be – this here list being not definitive! – stylistic diversity, making use of various folk elements, gravitational pull into Nordic soundscapes, and an urge to become integrated in the international jazz continuum.